Liturgy's Role in a Culture of Abuse

"It doesn't happen here."That is the response that many pastors would give if asked whether abuse is a problem in their church. According to a study done by Lifeway Research, "3 in 10 pastors (29%) believe that abuse is not an issue within their congregation." Because of this, very few pastors even mention the topic in church, which perpetuates a cultural issue that affects many within our congregations. To be at the forefront of addressing issues of abuse within the homes of our church congregants, churches must break their silence on the issue through liturgy and lament. What is Abuse?Abuse is often seen as an issue that only the outside world struggles with. But is it?Abuse is a word that is used in relation to several different ideas. There is physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. There is child abuse and spouse abuse. Each abuse term or name denotes a different type of mistreatment and often indicates different perpetrators, which makes it difficult to talk about the topic as a whole. Because the issue can be so broad and different complexities exist within each type of abuse, I will be exemplifying my arguments through statistics and stories about abuse specifically in relation to domestic violence. However, I would like to be very careful to clarify that domestic violence is not the experience of many abuse victims. Domestic violence is a small portion of the larger problem this article seeks to address. Though I am choosing to narrow the discussion to a specific type of abuse for the sake of space and clarity, I want to firmly acknowledge that men, boys, children, and girls are all affected by many types of abuse and my choice to narrow the discussion is not meant to illegitimize those experiences or state that one type of abuse is more important than another.The National Domestic Violence Hotline says:

"Domestic violence (also called intimate partner violence, domestic abuse or relationship abuse) is a pattern of behaviors used by one partner to maintain power and control over another partner in an intimate relationship."

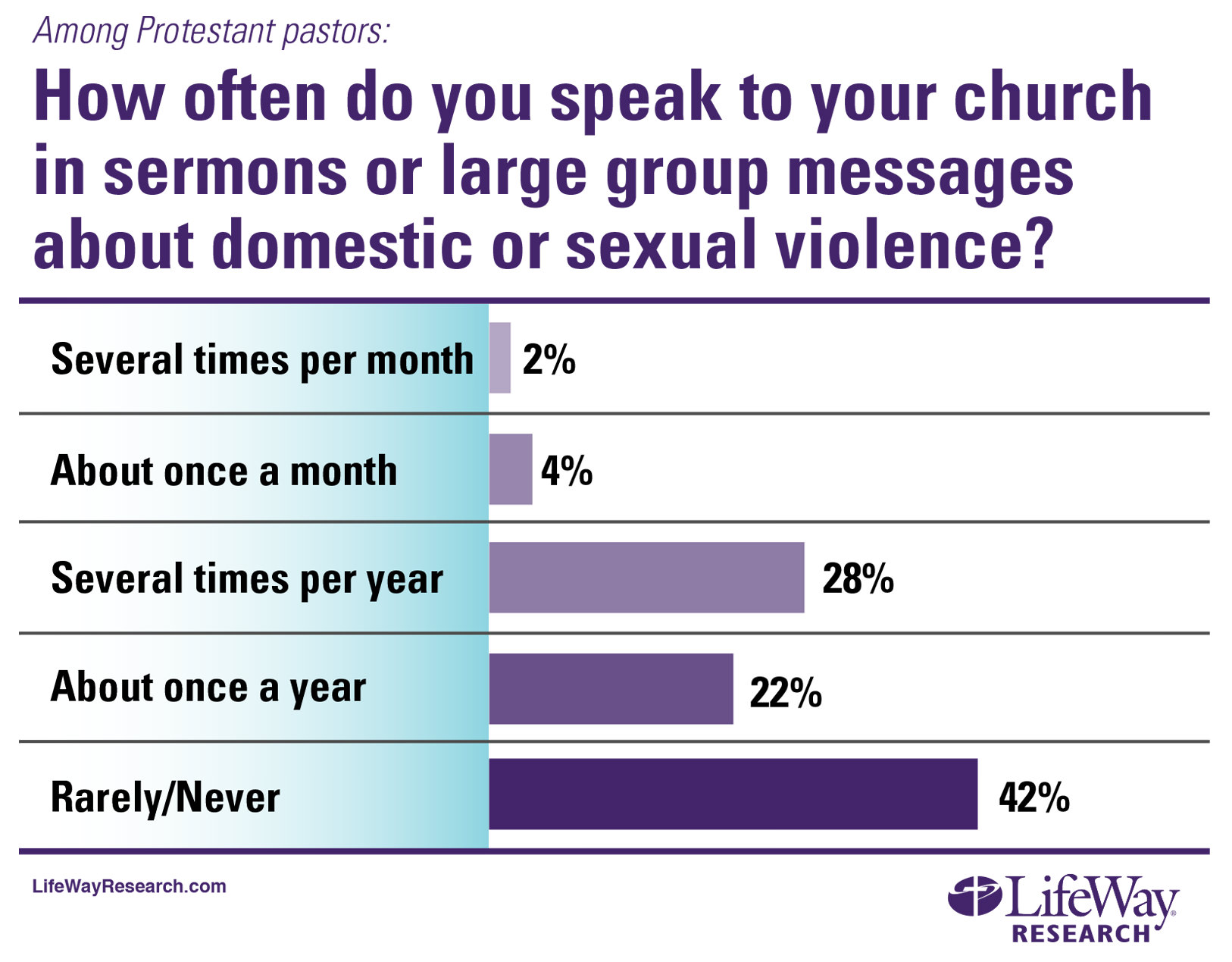

To understand domestic violence as a whole, consider this image created by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Program.  It is intended to communicate how abusive behaviors go beyond just hitting and punching. There is a cycle of violence and control going on that includes many more elements. These elements may look different in instances of other types of abuse. For instance, a sexual predator might "groom" his or her victim by manipulating them to feel cared for through the unhealthy relationship. This is a different way of using control, and later violence, to get what he wants. Understanding what abuse and domestic violence mean and include will be essential in our further discussion. For more information, look here, or here, or here. How does this fit in with the church?Apart from the 29% of pastors who believe that abuse is not an issue, almost half of pastors (47%) say they "don't know if someone in their church has been a victim of domestic abuse in the past three years." And while 87% of pastors believe that someone "experiencing domestic violence would find our church a safe haven", only two-thirds talk about it once a month or less. So are they right? Are churches really free of this issue?According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Approximately 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 7 men in the U.S. have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime." With these statistics, even a small church is likely to include people experiencing this issue. No pastor should assume their church is safe from abuse. So why, then, isn't it talked about?

It is intended to communicate how abusive behaviors go beyond just hitting and punching. There is a cycle of violence and control going on that includes many more elements. These elements may look different in instances of other types of abuse. For instance, a sexual predator might "groom" his or her victim by manipulating them to feel cared for through the unhealthy relationship. This is a different way of using control, and later violence, to get what he wants. Understanding what abuse and domestic violence mean and include will be essential in our further discussion. For more information, look here, or here, or here. How does this fit in with the church?Apart from the 29% of pastors who believe that abuse is not an issue, almost half of pastors (47%) say they "don't know if someone in their church has been a victim of domestic abuse in the past three years." And while 87% of pastors believe that someone "experiencing domestic violence would find our church a safe haven", only two-thirds talk about it once a month or less. So are they right? Are churches really free of this issue?According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Approximately 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 7 men in the U.S. have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime." With these statistics, even a small church is likely to include people experiencing this issue. No pastor should assume their church is safe from abuse. So why, then, isn't it talked about? According to Bob Smietana, "domestic violence is the one pro-life issue that Protestant pastors almost never talk about." Researchers in the same study found that 4 in 10 (42%) pastors “rarely” or “never” speak about domestic violence.According to a study conducted by Nancy Nason Clark, 95% of church women report that they have never heard a message on abuse.There are reasons that abuse is not talked about. Because it is a complex issue, most people don't know how to talk about it. Many pastors also have no idea what to do about it. 45% of churches "have no plan for how to respond if someone shares they have been experiencing domestic violence."There are many likely contributing factors as to why people may be reluctant to address the issue. One factor may be a general ignorance on the topic. Unless you have experienced it firsthand, most people truly aren't educated on what abuse is and how prevalent it is. I am continually amazed at how many people will tell me, "I didn't know that was abuse" or "She doesn't seem like the type of woman who gets abused." The reality is that there is no type, and that abusive behavior spans much more than just someone hitting you. If pastors aren't educated on the issue, of course they wouldn't think to mention it.It is also likely that people are uncomfortable talking about abuse. This could be because of unresolved trauma in their own background, in their family, or a general unfamiliarity with this dificult topic. No matter the reason, pastors may shy away from the topic either because it makes them uncomfortable or because they don't feel well equipped to know what to say. This fear of saying the wrong thing may lead to silence, which is even worse.This silence has immense implications for church congregations throughout the U.S. To understand why silence has such devastating ramifications, we must first understand how liturgy works. Liturgy in the ChurchOne of the most basic components of a local church is liturgy. This word brings thoughts of kneeling benches and spoken creeds to most people's minds, but it actually includes much more than just the religious practices and traditions that we would consider to be "liturgical." James K.A. Smith is a leading scholar in the discussion of how liturgy shapes culture. Much of his writing and speaking is centered upon the concept that what we do shapes who we are.In this discussion we are defining liturgy in a broad sense, stating that it is what we do when we gather together. This would mean that every church has liturgies that it practices. Some churches read prayers together or recite creeds communally. Others, much like those that I grew up in, start their church service with the five minute meet-and-greet time. This is a liturgy, just as reciting the creed is a liturgy.So, then, if we believe that what we do when we gather together shapes who we are, we must be very intentional in choosing what those things will be. Everything communicates something. This is at the foundation of why liturgy matters. The five-minute meet-and-greet is not just a thing to pass the time; it communicates something about who we are and who God is.Everything else we do when we gather together communicates something about who we are and who God is too.James K.A. Smith states that,

According to Bob Smietana, "domestic violence is the one pro-life issue that Protestant pastors almost never talk about." Researchers in the same study found that 4 in 10 (42%) pastors “rarely” or “never” speak about domestic violence.According to a study conducted by Nancy Nason Clark, 95% of church women report that they have never heard a message on abuse.There are reasons that abuse is not talked about. Because it is a complex issue, most people don't know how to talk about it. Many pastors also have no idea what to do about it. 45% of churches "have no plan for how to respond if someone shares they have been experiencing domestic violence."There are many likely contributing factors as to why people may be reluctant to address the issue. One factor may be a general ignorance on the topic. Unless you have experienced it firsthand, most people truly aren't educated on what abuse is and how prevalent it is. I am continually amazed at how many people will tell me, "I didn't know that was abuse" or "She doesn't seem like the type of woman who gets abused." The reality is that there is no type, and that abusive behavior spans much more than just someone hitting you. If pastors aren't educated on the issue, of course they wouldn't think to mention it.It is also likely that people are uncomfortable talking about abuse. This could be because of unresolved trauma in their own background, in their family, or a general unfamiliarity with this dificult topic. No matter the reason, pastors may shy away from the topic either because it makes them uncomfortable or because they don't feel well equipped to know what to say. This fear of saying the wrong thing may lead to silence, which is even worse.This silence has immense implications for church congregations throughout the U.S. To understand why silence has such devastating ramifications, we must first understand how liturgy works. Liturgy in the ChurchOne of the most basic components of a local church is liturgy. This word brings thoughts of kneeling benches and spoken creeds to most people's minds, but it actually includes much more than just the religious practices and traditions that we would consider to be "liturgical." James K.A. Smith is a leading scholar in the discussion of how liturgy shapes culture. Much of his writing and speaking is centered upon the concept that what we do shapes who we are.In this discussion we are defining liturgy in a broad sense, stating that it is what we do when we gather together. This would mean that every church has liturgies that it practices. Some churches read prayers together or recite creeds communally. Others, much like those that I grew up in, start their church service with the five minute meet-and-greet time. This is a liturgy, just as reciting the creed is a liturgy.So, then, if we believe that what we do when we gather together shapes who we are, we must be very intentional in choosing what those things will be. Everything communicates something. This is at the foundation of why liturgy matters. The five-minute meet-and-greet is not just a thing to pass the time; it communicates something about who we are and who God is.Everything else we do when we gather together communicates something about who we are and who God is too.James K.A. Smith states that,

I definitely believe there’s something at stake when we gather communally in these worship practices. We can do something collectively that we could not do individually. The gathering of the body of Christ is not just a collection of individuals who are now having their own individual relationship with God. It is the forging of a people who now are acting communally and collectively.

In this way, what we do when we gather together teaches us how to approach God, how to interact with others, and how to understand the self. It teaches us how to orient ourselves before the Lord. Prayer is an example of this. The way that we hear prayer modeled in church is how we end up praying to God when we're by ourselves. Even this teaches us elements of who God is, whether what is communicated is correct or not. Even the way we worship God and the things we worship Him for communicates to us what we value about Him and in what manner we approach Him.In a lecture given to Wheaton College on September 1, 2016, Smith expounds upon this idea by saying,

There is a way that you catch the gospel. There is a know-how about Jesus that is absorbed by giving yourself over to the tangible practices of Christian worship. So that, in worship, you learn something about the gospel that you couldn’t learn in any other way; that would never ever be the equivalent of merely absorbing the information about the Scriptures, but it’s a kind of know-how that you catch precisely because you are immersing yourselves in these rythymns. It's as if carried in these practices of Christian worship is an understanding of God that we know on a register that is deeper than the intellect. It's an understanding of the gospel on the level of the imagination that changes how we even comport ourselves to the world. It changes your feel for the world. It seeps into you at this level that you cannot ever quite articulate, but that reshapes everything that you do.

This is a powerful statement. If this is truly the power of Christian liturgy, then we must stop to recognize that even in our exemption, we communicate. What we don't talk about communicates just as much about who we are as what we do talk about. If abuse is such an issue in our world, and yet the church is silent on the issue, this has liturgical implications. What does this communicate to the abuse victim? Where Our Church Service Falls ShortBy and large, it is not just abuse that churches fail to address well. In most traditions, there is very little room to suffer communally. Think about it: what's in the average contemporary church service? We open with some contemporary worship songs, many of which we could categorize as praise music. How many of these songs embrace suffering? I would say that the majority of them focus more on upbeat music, a happy tone, and very simple lyrics. This is not necessarily negative, but when this is all we have, we lack the portion of music that helps us sing to the Lord when we are in pain. A lack of theological depth seems to lean towards simplified worship lyrics.What comes next? Maybe a few announcements about the upcoming church potluck or the baptism service next week. Then possibly the five minute "shake a friend's hand" time. Then comes another set of worship songs with vague lyrics and then the preacher comes up to preach the sermon. Most sermons rely heavily on quippy sermon illustrations to keep the congregation's attention, and then communion takes about ten minutes as the plate is passed and the elements are consumed. Maybe a few more worship songs, or a transitional prayer, and then the service is done. Church's service orders vary widely by denominational background and liturgical tradition, but in my experience, most contemporary services mirror the model just described. For most of the service, the congregation is either sitting and listening or singing happy songs. Where is there space to lament communally? Do we even know what that looks like? Suffering in the ChurchOur churches' lack of communal lament is not due to a lack of rich theology on the topic. The Bible speaks very clearly about suffering and lament. There is no lack of discussion about suffering. In fact, we serve a suffering Savior who chose to enter into our pain and dwell with us. He set an example for us to live by. He did not avoid suffering. In fact, Hebrews 5:8 says that he learned obedience through what he suffered. He took the cross for us, and He calls us to take up our cross and follow him. Nowhere in the Bible are we promised we will not suffer. In fact, James tells us to consider it pure joy when we face trials of all kinds. Shouldn't the church, then, have space in its weekly practices for those who are suffering? LamentThe Bible also offers us a rich theology on what our response to suffering should be. The Psalms offers us a language with which to approach God in our suffering. Rather than merely praising Him for the good times, God desires that we draw near to Him in our pain as well. The act of lamentation is a way to talk about our suffering with God. It gives us words to express our otherwise word-shattering pain. The Psalter yells at God and mourns to God about the circumstances causing him pain. Sometimes he is surrounded by enemies, and sometimes he is close to death. There are times when his bed is drenched with his tears. And yet, He talks to God about all of it. How often do our churches train us in how to talk to the Lord about the most difficult parts of life?I know my church never did. I hadn't even heard the word lament until I arrived at Bible school. I was taught to minimize my pain, saying it was okay when it wasn't. I felt like I had to ignore my pain or forget about it, rather than verbalizing it before my Father who could handle it. I realize now that this attitude is based on a very shallow understanding of who God is. Do we think He'll be angry at us for honestly expressing how we feel? Do we think that He cannot handle our doubt, our pain, or our anger? Throughout the entirety of the Bible He shows Himself to be the God of the broken. Why would we think we're any different? ConfessionAlong with this proper understanding of who God is, the Bible offers us a proper understanding of who we are as broken, sinful people. Much of our suffering is due to the sin of others, but some is due to our own sin. James calls us to confess our sins to one another. This provides a healthy outlet to confess and be affirmed in our true identity, while still acknowledging our insufficiency before a Holy God. If confession were practiced regularly on a congregational level, what culture would this establish within our churches? Because we are what we do, maybe this would create a culture that tears down pride and false masks of perfection and instead instigates a normative vulnerability between believers.So we see that the Bible is very vocal on a theology of suffering, lament, and confession. Because of these things, and because we are what we do, practicing this theology congregationally would establish a culture of vulnerability where there is space for those suffering around us, no matter what type of suffering they encounter. What about Abuse?In relation to those suffering from abuse, though, the Bible speaks clearly to their pain. Not only does it communicate God as a God who cares for the brokenhearted and draws near to those in need, but it also includes examples of biblical characters whose pain was quite similar in nature to those facing abuse today.Joseph experienced horrible treatment from his brothers. Genesis 37 says that they could not speak kindly to him. Their hatred of him led them to plot his murder, strip his clothes off, throw him in a ditch, and sell him as a slave. Hagar faced severe mistreatment at the hands of Sarai, as well as sexual abuse at the hands of Abram. Tamar was raped by her own half-brother. The story of Abel recounts the brutal attack of one brother against another that ended in death. Even Jesus faced all kinds of mistreatment, from verbal assault to physical beatings. The Bible is packed with stories of real people facing real abuse. Therefore, the church has no precedent to turn away. What The Church CommunicatesWith the understanding that the Bible offers a clear and rich theology for suffering and our response, we can acknowledge that our silence on this issue doesn't really make sense. Also, with the understanding that what we do communicates truth about who we are and who God is, we must evaluate how what we do (or don't do) is wrongly communicating.If abuse is really so prevalent in our churches (1 in 3 women, 1 in 7 men) and yet the church is silent on the issue, what does that communicate? We lie to ourselves if we think our silence is not communicating something. Think of the woman who faces physical abuse every week. She comes to church searching for how God fits into her reality. If we are silent, we are communicating to her that her suffering doesn't matter. She is being encouraged to suffer in silence without speaking up. Meet BettyIf the deepest pain in her life is "something we just don't talk about here" then how will she learn to bring it to the Lord? How will she learn what the Bible says about it? Instead, many biblical principles are miscommunicated to her. A pastor preaches a sermon on marriage. He feels the need to expound upon the principle of biblical submission because our feminist society has attached a negative connotation to what was meant to be a beautiful thing. And so, with this tension in mind, the pastor spends twenty minutes of his sermon hashing out what biblical submission was meant to be. In doing so, the woman listening - let's call her Betty - internalizes the wrong message.You see, Betty, as with most abuse victims, does not have a very high view of herself. For years her husband has told her what a worthless piece of shit she is. And though at first she was determined to let the insults slide off her back, over time some of them began to stick. This is a common principle of brain-washing. If someone tells you something enough, you start to believe it.So think of what mindset Betty might come to church with every week. She may think she is not worthy of love. She may think that her role in her marriage is to wait hand and foot on her husband. She has been conditioned to fulfill his every need to avoid the verbal assaults and physical attacks she would get if she didn't. She feels like an inconvenience and a burden. She will not share how she's feeling unless someone asks, communicating that she will not be a burden by sharing. She has a negative view of men in leadership and a fear of power. She is not coming to church to learn how to thrive in her faith because she is just trying to survive right now.So if Betty is sitting through a sermon on biblical submission, what is she going to internalize? The words spoken may only affirm that she is doing the righteous thing by waiting on her husband constantly. She will see this as service to him, or a way to love him well. To her, Jesus washing his disciples' feet is a lot like when she spends hours laboring over her husband's favorite dinner, only to have it thrown against the wall because it is lukewarm by the time he comes home. She thinks that her marital issues are just an issue of her not being selfless enough or humble enough. To her, the way that dinner ended was her fault. If she had only thought to keep reheating his food every fifteen minutes while she waited for him to come home, he would have been happy. She had failed to love him well. So What?Do you see how a simple talk on biblical submission can be misunderstood? This is because what we do shapes who we are. Betty is only coming to church once or twice a week. The rest of the week, she is being shaped by the nasty words and fear tactics of her husband. And if the church is utterly silent on the topic of abuse, it will only become a normalized part of her life that is integrated with her spirituality.Think of how people like Betty might internalize certain passages of Scripture. Think about Matthew 18:21-22 in which Jesus tells his disciples to forgive others up to seventy-seven times. Or think of Matthew 5, which tells us to turn the other cheek if we are slapped, or to love our enemies. What kinds of theologies do you think abuse victims form from these verses?Statistically, we know that abuse victims are not likely to leave an abusive situation. This is because of several factors. Firstly, there is often a false loyalty to the abuser, who is often a family member. Even though the abuser is mistreating the victim, he/she will still fight to maintain loyalty because family is a high value to them. Betty wants to escape the violence, but not the man she married. She loves him, and she knows deep down that he loves her too. Meet the AbuserThis is another thing that is important to understand about abusers, though we have not touched on typical abuser behavior yet. Abusers are manipulative, and abuse in its very nature is cyclical. There is a honeymoon phase where the couple is in love and all is right. Then tension starts to build. The woman feels like she's walking on eggshells, not knowing what will set her husband off. Throughout all of this, he is using control tactics and fear tactics to manipulate her behavior. Then comes the attack. He's had it and he lashes out verbally and physically. His anger often gets the best of him, which he does feel somewhat bad about. He didn't expect to lash out to the degree in which he did, and he apologizes profusely at the sight of his battered wife. He reminds her that he loves her and uses guilt to convince her it was her fault. "If you wouldn't push my buttons so much, this wouldn't happen." Because of this cycle, the abuse victim believes 1) that this is her fault, and 2) that the abuser really does love her, and if she stays this relationship can be fixed. Her husband is not horribly evil all the time. In fact, it's possible that he is incredibly respectable most days. It's just the few days he lashes out that hurt her. So it's easy for her to rationalize staying. A Theology of ForgivenessBecause of the complex dynamics of this abuser/abuse victim relationship, Scriptures about forgiveness are often misunderstood. If Betty truly believes that the abuse if her fault, of course, she would try to be more righteous next time. She feels that Matthew 5 is a direct command for her to humbly take the abuse and forgive her abuser. What else would "turn the other cheek" mean to someone who is physically hit quite regularly? What might "love your enemies" look like if not serving your abuser dinner and forgiving his offense over and over - up to seventy-seven times?Though most of this is unintentionally communicated based on the presuppositions that have been normalized for an abuse victim, some of these things are actually spoken to her. The first few times that many victims open up about the abuse they are experiencing, it is common for one of the first questions asked within the church to be, "Have you forgiven him?" This is a heinous question to ask someone who has faced such life-shattering pain. It automatically tells the victim that her pain and healing comes second. It shifts the focus to immediately care for the abuser. In an abuse situation, where healing takes years, forgiveness comes much later in the process. The first thing an abuse victim needs is to be heard and legitimized.Another common miscommunication within the church in relation to abuse is its concept of gender roles and headship in marriage. Not only can this concept be misunderstood by the victim so that she feels obligated to submit to a violent and demeaning man who causes her real physical danger, but this concept can also be used by the abuser to defend himself. In all of my research on abuse and the church, this is one of the most common occurrences. Church-going abusive men use the concept of headship in marriage to manipulate and control their wife. "Why can't you just submit and respect your husband?" If preachers aren't careful, they can unintentionally be giving the abuser more ammunition to control their wife.So what do we do with this information? Pastors obviously would not agree with these wrong understandings of key Biblical passages and most did not say anything that would have been understood this way by most congregants. Isn't it just the couple's problem if they misheard the preacher?My answer is no. Fixing this problem is actually quite simple. It merely requires a preacher to be intentional in his communication of these passages. When talking about forgiveness, he must clarify what forgiveness IS NOT. This would be a perfect time to go say something like, "If you are in an abusive situation, this is not a call for you to let his behavior go. It is wrong and you should not be treated like that. Forgiveness does not mean you stay in a situation that causes you danger. If you are in this situation, we grieve with you and desire to walk with you. If this is you, talk to someone today."It would be a simple couple of sentences, but it would go a long way. It would allow for a doorway out. It does not allow a woman to hear the word forgiveness as a call to tolerate abuse. And it tells her that this treatment is wrong. It legitimizes her feelings that she shouldn't be treated like this. It tells her that the church is on her side and that they care about the abused, rather than remaining silent on the topic.This, of course, is not the complete solution. Talking about it often and cultivating an orientation towards lament and confession will create a culture where communal healing can take place. Just tacking a few sentences on to the end of your sermon is not the answer. Those sentences must be connected to the culture which exists within your community.When talking about submission, gender roles, or headship in marriage, there is a similar opportunity. Pastors should clarify the difference between biblical headship/submission and a domineering, abusive relationship. There is a difference, but unless it is directly spoken into, the lines can get blurred. Above all, pastors need to verbally rebuke abusive/domineering behaviors from the pulpit. Call it as it is: sin. Rebuke men who use the Scriptures to defend their behavior. This again lets the abuse victim know that the church cares and fights for what is right, as well as telling the abuser that the church refuses to help him mistreat his victim. Community CommunicatesApart from just the sermon itself, the church's liturgy and lived community communicates to abuse victims. One thing that is important to note is that it takes an incredible amount of courage to even tell someone that you have been abused. This is partially because the victim blames themselves, and partially because it is such a deeply painful thing that they don't want it to be handled poorly. Unfortunately, the church's lack of knowledge on the topic often leads to the later.The first problem is that sometimes the victim is not even believed. This is often because of the manipulative nature of the abuser. Like we discussed before, it is possible that the abuser is an incredibly respectable person most of the time. It's also possible that he is manipulative enough to cover up the rest of the time or make the victim look like an exaggerating, crazy, fool if she speaks up. Especially in a situation where the abuser and the abuse victim go to church together, the abuser is often a well-respected member of the congregation.The study cited earlier shows that 43 percent of pastors "are unwilling to say whether or not they would believe abuse took place." This is a mistake. The rule in these cases is to always believe the victim. Because abuse is such a difficult thing to disclose, it is not common that someone would make it up.Another mistake in how these situations are handled is that the abuser is often treated as the ministry priority. Even if abuse is happening and the victim is believed, the victim's healing is seen as secondary. Ministry leaders tend to feel like it is their job to "fix" the abuser, and so they put all their time and energy into ministering to the abuser. Whether this works or not is entirely dependent on whether the abuser is repentant or is just manipulating the church leadership to think they've changed.However, what happens with the abuse victim in the meantime? Her pain is illegitimized. Telling an abuse victim that you're "working on it" when she is trying to tell you what happened is not what she needs. That only silences her. She doesn't need you to fix it, she needs to be heard. She needs someone else to listen to her pain and grieve with her, rather than strategizing on how well her abuser is doing in Bible study lately. She has been silenced enough. That is not your job. Your job is to respond by listening and grieving.Of course, there is a point in which you may have to encourage her to leave the situation or find further help elsewhere, but you cannot set her needs aside until you've fixed him. And she came to you for a reason. Do not treat her like a secondary priority to her abuser. This only communicates things you do not want to communicate to her about who she is and who God is in this process of healing.The third thing that pastors must not do in an abuse situation is trying to fix it through marriage counseling. Hopefully, you understand some of the reasons behind this based on what we have already said about abuser/victim relationships. How can you expect a victim to be honest when her abuser is in the same room? What will likely happen is that the abuser will be manipulative and make himself look good. He will make her look crazy or explain that she's just exaggerating for attention or due to hormones or *insert another life event.* The minister will believe him and because she doesn't argue - remember, she can't? - he assumes that he has reached the root of the problem. She is left once again silenced because if she says what's really happening in front of him, he will beat her later for making him look bad. An abuser is self-preserving above all else. Most are narcissists and truly don't see the err in their ways. They feel justified in acting as they do because of their "unruly" wife.

- They need a church that is going to stick with them for the long haul.

- They need a church that does now squirm at suffering.

- They need a church that gives them room to be in pain.

- They need a church that is willing to be patient to walk them through a healing process full of anger, tears, doubts, and soul-crushing questions about themselves and God.

- They need a church that is safe for them to be vulnerable without being exploited in the process.

- They need a church that will fight for them and will offer them the resources they need to stay out of harm's way.

We must intentionally move from a liturgy of silence to a liturgy of lament.

There is no one formula to implement this, but here are a few ideas:1. Incorporate liturgical prayers for the abusedDepending on your church tradition, this may not fit in your normal service. However, written prayers are a great way to voice the pain of those who may not even be able to voice it themselves. Maybe after a sermon on suffering or a sermon about forgiveness, a person from your congregation can come up to the front and read a liturgical prayer for those who are dealing with abuse. Some examples can be found in chapter 20 of THIS book.2. Mention it during communionCommunion is a time of remembrance. While we often sterilize it in our minds, it is a remembrance of a very violent, gory event. Jesus is no stranger to abuse. He was beaten, spit on, verbally assaulted, and ultimately killed. He is perhaps one of the greatest comforts to those who have lived through horrible abuse because He knows their pain and can meet them in that. Communion is an excellent time to spend time as a congregation dwelling on what Jesus suffered and how he meets us in our own suffering from abuse. Jesus offers hope into even the most hopeless situation. Communion is an excellent time to incorporate our rich theology into our practiced liturgy.3. Offer prayer counselorsAfter a particularly difficult sermon or a time of dwelling on pain it is a good idea to offer prayer counselors. The pastor could give a short monologue about those still suffering and then point them to the prayer counselors who are present to pray with and for them. This may seem like a small thing, but for those who don't even know how to start bringing their pain before the Lord, being prayed for can be powerful.4. Provide testimoniesThe Lord created us to be people who make sense of our world through stories. This is why testimonies are so powerful. Testimonies offer true stories of other people who have been through similar circumstances that we may one day face. Offering time for a woman who has healed from an abusive relationship to share her story is both healing for her, as she gives voice to a story that had been previously silenced, and it offers other people in similar situations to see that God cares for the abused. It communicates that the church cares about abuse. And it shows a victim that healing is possible.5. Offer a healing ministryMany churches have created healing ministries which offer an intentional and safe place to come and talk about these types of wounds while gaining support from others. Each church is different, but the power of small group ministries in a healing process is valuable.6. Have resources on handA wise man once told me that if a church is going to start mentioning abuse, they'd better have resources ready. This is important. Because of the complex nature of many abuse situations, one pastor cannot handle every aspect. You need to know about women's shelters in the area, counselors who specialize in abuse, resources to provide, and support groups to get involved in. Addressing abuse in our liturgy is an important part of communicating who we are and who God is in light of this injustice, but the first step is very simple: break the silence. To see what this looks like in real life, view my creative project HERE. Apart from the studies and articles cited in this chapter, check out these books and resources for more information:No Place for Abuse by Catherine Clark Kroeger & Nancy Nason-ClarkSetting the Captives Free: A Christian Theology for Domestic Violence by Ron ClarkBeyond Abuse in the Christian Home: Raising Voices for Change by Catherine Clark Kroeger, Nancy Nason-Clark, and Barbara Fisher-TownsendDomestic Violence: What Every Pastor Needs to Know by Al MilesBetween Pain and Grace: A Biblical Theology of Suffering by Gerald Peterman and Andrew J. SchmutzerMORE RESOURCES